Why, of course you’re not going to believe me. I mean, only old people find these little shits endearing anyway. I haven’t met anyone under the age of thirty who didn’t think they were absolutely nightmare-inducing. But hear me out – I have some other reason to hate garden gnomes.

It all started when I was about eight. You see, I had a pretty regular childhood. My parents never divorced, we had a suburban house, and my four grandparents were alive until recently. Oh, of course there was some family drama – whose family doesn’t have any? But it never got bad enough that we had to cut ties with relatives. My grandma’s house was as typical as our life: decently sized, with two guest rooms, a big kitchen, a garden with a vegetable patch, a swing for us kids, and a garden gnome. Now before that story started, I had no hard feelings towards that gnome. It was just some weird decrepit doll I wasn’t allowed to play with because, despite looking like a toy, it wasn’t one, according to my grandma. I didn’t pay it too much attention, since there were much more exciting things to do – namely the swings, and in the summer the strawberries ripening, for example.

A bit of a tradition in our family was that I’d spend a part of the summer holidays there with my cousin Lily. We were the same age, being born exactly six months apart (a fact our families loved to bring up at every reunion), and got along well despite our very different personalities, as is often the case with children. She was this fun, extroverted kid who would constantly drive the adults crazy with her questions while I was quiet, a bit of a coward, and very reasonable. Our parents liked to say we “brought out the best in each other”. I don’t really know about that – what I remember is Lily pushing too hard on the swing and falling down once, in a very dramatic way, shattering one of her front teeth. I did warn her, of course – but did she ever listen to what I had to say?

Anyway. Back to the gnome. This happened in the early 2000’s and, as I said, I was eight. I had just arrived to my grandma’s to spend three weeks there before my parents had their days off and would join us. Lily was there already. I got off the car and she ran towards me, screaming with excitement.

“Notice any change?”, Lily asked, her eyes bright with mischief.

“Now, Lily, don’t spoil the surprise”, Grandma warned.

I looked around.

“It’s in the garden!”, Lily shouted. “You’re getting warmer!”

I looked around and approached a rhododendron bush. Everything seemed to be as I remembered. I turned a corner and saw it.

“The garden gnome! You… changed it?”, I asked, confused.

Before Grandma could say anything, Lily shrieked.

“We repainted it! And she let me choose the colors!”

The gnome’s overalls were indeed bubblegum pink instead of their regular denim blue.

“That’s nice”, I said. And really, I didn’t know what else to say. It was a bit weird to see the gnome in that state, as I was so used to its old appearance – its face was more defined, but really that was all.

We all went inside and had a late lunch – it was about 2:30pm.

Now the weird things started right after lunch. Lily and I headed to the garden to play on the swings; she had been given a new bouncing ball by the neighbor and we were fighting over it. Suddenly I smashed the ball while it was in the air and it bumped into the shed’s door. We weren’t allowed in it, as it was full of sharp tools, dust and cobwebs, and so my grandma kept it locked at all times. Except that day, apparently. When the ball hit the old wooden door, it opened, ever so slightly. We stood there, abashed.

“Should we get inside?”, Lily asked.

“If we do so, grandma will ground us and tell our parents.”

“She doesn’t have to know.”

“But she will!”

“C’mon, Annie – just one minute! Don’t you want to see what’s inside?”

“But we’re not allowed”, I replied tentatively.

“Get back to grandma if you want, I’m going inside”, she decided.

That’s the thing with Lily: once she had decided she would do something, there was no stopping her. So I sighed and followed her in the shed – after all, I was curious too.

Now that I think about it, there was nothing remarkable inside the shed, and I can definitely see why adults didn’t want us in there. The sunlight glimmered over metals, all more or less rusty. Mostly there were bags of fertilizer and old garden tools. Nothing phenomenal, really. Lily closed the door and we were submerged in total darkness – there were no windows and no light bulb. I muffled a scream.

“I know what we’re gonna do!”, she whispered excitedly.

“Get out of there?”

“No, silly – I’m getting my glow-in-the-dark marbles!”

“Wait -”

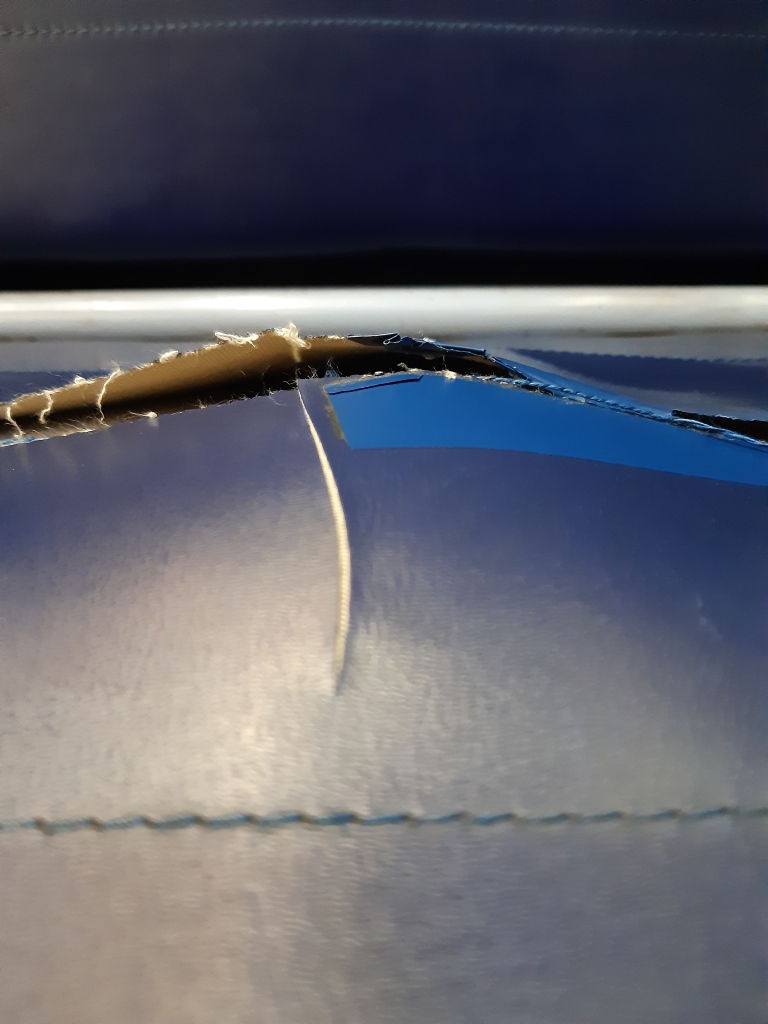

But she was already out. I stood there, frightened. I wanted to get out of the shed, but I could hear my grandma not that far away and I was afraid she’d see me opening the door. So I just… stayed here, praying that Lily would come back quickly. And then it… happened. Or rather started happening. I heard a scratching noise from the outside.

“Lily?”, I whispered. “Quit doing that!”

The scratching continued. It felt like claws on wood. No way that a child’s nails could make such a sound. Maybe Lily had brought some kind of instrument – a fork perhaps? – and was fooling with me. I called her name again, threatened to scream for grandma – no response. And then – I can still hear it – I heard one of the wooden planks being… torn apart. Granted, the shed was old, so it couldn’t have been too hard – but why would Lily do that? My knees gave out and I fell on the ground. And then – how is that even possible? – I saw some light. One of the planks had been ripped off and there was a tiny hole, or rather a split, in the wall, that let light enter the shed. I stared at it for what must have been a few seconds only but felt like whole minutes, and then… something… something was behind the split. Staring at me. It was a painted eye – a black eye. I could not but recognize it immediately. The eye rose up, still staring at me (or at least that’s how it felt), and through the crack I could see the whole shabby face… of the old garden gnome. I opened my mouth to scream and as soon as I did that, it just… disappeared. As if nothing had ever been there, staring at me through a crack they (or rather it) had just created. Finally regaining control over my body, I jumped on my feet and stormed out of the shed – and you may have guessed it: there was nothing outside. No old shabby gnome. No prankster cousin. Just the grass. At that moment the back door slammed and Lily started running towards me. She stopped dead in her tracks upon seeing my face.

“What’s wrong?”

“It’s not nice to scare people like that”, I accused her, although I was pretty sure that what I had just experienced was not Lily’s making.

“What are you talking about? I was just inside.”

I told her what I had seen, and showed her the crack – I think she was even more scared than me, actually. It was nice to have her believe me, because I knew no adult would. We went back to the gnome. It was still here, freshly painted, mocking us with its empty eyes, fake smile and pink overalls.

“You sure that’s not what you saw?”

“Yes. I saw the old gnome. The one that had paint peeling off its face.”

She frowned.

“Then I don’t know. We should ask grandma if she has some other gnome laying around. But first maybe check the shed?”, she proposed, her eyes brightening.

“Nobody’s gonna check the shed!”

“Alright, alright! I’ll ask her over dinner then.”

And that’s what she did. As I said, Lily was always good at getting the adults to give her information – she had been so involved in the whole repainting stuff her asking about the gnome didn’t seem to strike grandma as unusual.

“Grandma, do you have another garden gnome?”

“Another gnome? No, dear, just the one we painted.”

“Are you sure?”

She chuckled.

“Yes, of course. I’m not that old, I still know what I own!”

“Where does it come from?”, I asked.

“The gnome? Oh, I don’t really know. It was there when your grandpa and I bought the house. The previous owners had left a lot of things inside. We threw away most of it but ended up keeping a few. For example, the living room’s lamp was from them.”

We exchanged a silent look. Really, there was nothing more to ask about. When grandma asked us what we had been up to that afternoon, Lily made up a story on the spot – she had always had a talent for making stuff up – about our dolls being pirates fighting for a treasure (that was composed of her marbles). I suppose grandma believed her, as she didn’t ask any follow-up questions.

The rest of the holidays was peaceful. Sure, I had some nightmares about the gnome, and Lily and I still tried to elaborate theories about it – but mostly we played and argued. I’d not say we forgot about it completely: it just wasn’t our number one preoccupation anymore.

Still, I felt some kind of relief when we left, in addition to the habitual sadness. Hopefully I would stop dreaming about the gnome.

When we arrived home, after a five-hours long drive, it felt like waking up from some confusing, stressful nightmare. At that point I was pretty sure I had imagined it all. I mean, I’ve always had a rich imagination, and the sudden darkness had scared me so much I might as well have hallucinated the whole thing. Plus it made no sense I had seen the old version of the gnome – this was probably because I wasn’t used to its new look yet.

Anyway. My dad took my suitcase to my bedroom and I started unpacking. There were, neatly wrapped, all kinds of things I had taken home from Grandma’s place – a new doll, two books, various shells and funny-looking rocks, as well as scented paper. Under all that were the clothes, always the least exciting part of unpacking. I grabbed a pair of socks and felt something hard inside it. I unwrapped it, excited – my grandma often hid some tiny toys or a 10$ bill in my packages and suitcases. When I discovered what it was, however, I felt as if I had been thrown into a pool of icy water.

In my hands, staring back at me, was a plaster fragment – of an eye. The very same eye I had seen spying on me through the crack: black and shabby, with its paint peeling off. I dropped it off like it had burned me and it fell on the floor with a dull sound, where it kept staring at me. I felt hot tears rising under my eyelids and stomped on it, hysterically, until the gnome fragment was unrecognizable; I then managed to overcome my fear and gather the broken pieces. What to do with them? My first impulse was to throw them in the garbage can, but I quickly resolved against it – my parents could see them and get suspicious. Besides, I didn’t want this thing to stay in the same house as me. So I opened the window, made sure no one could see me, and threw the shards into the overgrown garden of the neighboring house (vacant at the time).

I sat on my bed, restless. My first thought was to call Lily; but at the time, cellphones weren’t as usual as they are now, and I would have needed to use the landline, which my parents would have known about since they insisted on listening to my phone calls. Now that I think about it, I should definitely have told my parents about the whole thing – but the childish fear of getting yelled at, maybe grounded, for entering the shed, as well as involving Lily, held me back. And I knew my parents wouldn’t believe me anyway – they’ve always made fun of people believing in anything even slightly supernatural and constantly told me to “stop lying” when, younger, I told them about my imaginary friends and their adventures. No, I thought, the safest thing to do now was to try and forget it all. So I didn’t tell anyone anything, finished unpacking, and joined my parents in the living room to watch some TV.

I didn’t sleep well that night. I don’t remember my dreams but I think I didn’t fall asleep properly before dawn; I was woken up by my mom around 10:30am. She entered the room as usual and opened the blinds.

“Good morning, Sleeping Beauty”, she said cheerfully, “your kingdom awaits you!”

I mumbled something unintelligible.

“Come on, do you see what time it is? You need to get back to a normal sleep schedule for when schools starts again.”

She walked towards my bed and stopped. I was facing the wall, but could feel her presence behind my back. She grabbed something placed on my nightstand.

“Good lord, what’s that? Annie, why do you have to keep such useless trinkets all the time? And what’s it supposed to be?”

I turned over. At first, I couldn’t see what she was holding, being blinded by the sunlight. Then it became clearer.

It was the gnome’s eye.

“What’s wrong?”, she inquired, seeing the look on my face.

“Don’t touch it!”

She raised her eyebrows.

“It’s, uh, mine. Lily… gave it to me. She… has the other half. It’s a cousin-best friends kind of thing.”

“Oh, okay then. If you say so. Anyway – get up before it’s too late for you to have breakfast.”

The whole day was a blur. It was clear I needed to get rid of the gnome’s eye – goodness, this is one ridiculous sentence, isn’t it? But it was also clear it wanted to stay in the house. To mock me, or… I didn’t even want to think about it. So I figured we needed to find a compromise. After hours of febrile thinking, I found what appeared to be the best solution: putting it in the attic. Nobody would find it weird to have some old broken thing up there, it would still be inside, and hopefully it wouldn’t come back to watch me sleep. I shuddered. When I asked my mom if I told keep it there, she looked surprised.

“Don’t you want to keep it at arm’s length? To remember your “cousin-best friend”?”

“If I do, I’ll keep playing with it and it might break. Look, it’s really fragile.”

It was the first time I lied to her with such conviction.

“Well, it’s your stuff, you can keep it wherever you want. Just don’t touch anything in the attic. I know where everything is stored and don’t want you to mess it up. Also, you could hurt yourself. Oh and, I don’t want you sneaking around there all the time, so if you keep it in the attic, remember you won’t be able to go play with it anytime you want to. Understood?”

I nodded and went back to my bedroom. I grabbed a shirt and used it to hold the eye. It was still staring at me, and although there was no particular expression to be found in it, I recalled the gnome’s face, constantly laughing for an unknown reason, and it felt like it was deliberately taunting me. I unlocked the attic’s door and turned on the light. It was a very regular attic in a very regular house, really, but not being able to hear my parents downstairs while being alone with the thing made me uneasy. I looked around, trying to find the perfect spot, and noticed an old suitcase we didn’t use anymore as its wheels were jammed. What decided me to drop it in that particular suitcase was that it got a lock – that was, fortunately, open. Obviously, I didn’t delude myself into thinking the lock would prevent it from doing whatever it wanted to do, but it was still quite reassuring to hear its clicking sound. Placebo effect, probably. I locked the attic door behind me, gave the key back to my mom, and for a while, that was it.

Of course it took some time before I could sleep normally again – to be honest, I’m not even sure to this day my sleeping pattern is something we can call “normal” – but the eye seemed to accept its new place and never showed up again. I avoided the attic on the pretext of being afraid of spiders and, as years passed, I thought less and less about that adventure. Actually, I almost managed to convince myself (once again) that I had made the whole story up – after all, my childhood was pretty boring and I could’ve used the thrill. I even wondered for a while if it could have been a psychotic episode, but nothing similar happened to me afterwards and the research I did on the question revealed that psychosis often starts manifesting during late adolescence or early adult years. Anyway – I also never told anyone this story before, and I would have kept things as they were if it weren’t for what happened last month.

I graduated last June. I found a job after a few months of job hunting – I admit I got lucky – and decided to move out. My parents initially wanted to leave my bedroom as it was to make sure I would feel welcomed when I’d visit them but I convinced them to use it as a spare guest room, which was lacking. I started packing my stuff. At the beginning, it was easy enough to determine what I’d take with me, and what should be thrown away; but eventually I stumbled upon some items (mostly toys) which, while having too much of a sentimental value to be simply thrown away, would be a waste of space and energy to take with me at my new place. I asked my parents for advice – should we give them away?, and they told me I should simply put them in the attic, at least for a while. Who knows, I might start a family a few years from now, and then I would be glad to still have my old toys to give to my child!, they reasoned. I felt uneasiness crawling up my skin at this idea but agreed, as this was obviously the best option. Had it been only a few years before, I would simply have asked my dad to move the boxes to the attic; but he had unfortunately hurt his back when I was still in college and thus wasn’t allowed to lift heavy objects or bend for too long. As for my mom, I knew she’d have made fun of me for still being scared of the attic – our relationship isn’t that great, if I’m honest, and I’d rather have faced the attic and whatever was in it than give her more reasons to call me a coward in front of people. I know it’s childish, and I’m not really sure how we even got there in the first place, as we were pretty close when I was younger, but it is what it is, right? So, long story short, I ended up taking the boxes to the attic myself.

I unlocked the door and turned on the light, looking around to see where I could leave them – I had hoped there would still be enough room in the front so that I wouldn’t have to get too close to the old jammed suitcase but unfortunately, it wasn’t the case. So I started walking towards the end of the room until I could see the suitcase.

The light bulb was too weak to properly light the whole room, but I could see that something had been placed at the top of the suitcase. I sighed, relieved – it was clearly too big to be the gnome’s eye. However, as I still needed to find a spot for my boxes, I kept going. As I approached, I could distinguish a silhouette in the dim light of the attic. A silhouette that looked humanoid, with a pointed hat. I let go of my boxes. Overhanging the suitcase was the old garden gnome, intact, with its blue overalls and its paint that was flaking off, grinning, and staring directly at me.

I don’t exactly remember how I got out of the attic. I left the boxes where they had fallen down, locked the door, and didn’t tell my parents anything. Now you might be wondering why I am telling you this, you who are total strangers, when I kept quiet for so many years and didn’t even tell my relatives what happened. Am I crazy? I don’t think so. As I mentioned before, I’m not showing any symptom of mental instability, whatever that means. I never have, really. No, if I’m telling you the whole story now, it’s because I need advice. Should I tell my parents about all of this? Letting them know they most likely have a haunted garden gnome (if that thing really is a garden gnome) in their house? I’m conflicted – on the one hand, I of course don’t want them to get hurt, and who knows what that thing is capable of – but on the other hand, I don’t want them to freak out (maybe for nothing) when they’ve spent the last fifteen years unbothered. And before you tell me to get back there and destroy the gnome – given what happened when I broke the eye and threw it away, I’m not sure that would put an end to it; actually, I’m afraid it would only make it angry and craving retaliation. I’m also afraid of it following me to my new home, obviously. I’ll keep you updated. So, yeah – in need of a few tips and opinions about all this, please.

TL;DR: I’m apparently being haunted (?) by a garden gnome since I’m 8. What should I do?